Студопедия КАТЕГОРИИ: АвтоАвтоматизацияАрхитектураАстрономияАудитБиологияБухгалтерияВоенное делоГенетикаГеографияГеологияГосударствоДомЖурналистика и СМИИзобретательствоИностранные языкиИнформатикаИскусствоИсторияКомпьютерыКулинарияКультураЛексикологияЛитератураЛогикаМаркетингМатематикаМашиностроениеМедицинаМенеджментМеталлы и СваркаМеханикаМузыкаНаселениеОбразованиеОхрана безопасности жизниОхрана ТрудаПедагогикаПолитикаПравоПриборостроениеПрограммированиеПроизводствоПромышленностьПсихологияРадиоРегилияСвязьСоциологияСпортСтандартизацияСтроительствоТехнологииТорговляТуризмФизикаФизиологияФилософияФинансыХимияХозяйствоЦеннообразованиеЧерчениеЭкологияЭконометрикаЭкономикаЭлектроникаЮриспунденкция |

Methods of Phonological AnalysisСтр 1 из 13Следующая ⇒ Organs of Speech The organs of speech are: 1) the mouth cavity; 2) the nasal cavity; 3) the pharynx; 4) the lips; 5) the mouth; 6) the teeth; 7) the tongue; 8) the larynx; 9) the roof of the mouth. The roof of the mouth is divided into the alveolar ridge, the hard palate, the soft palate with the uvula. The surface of the tongue can be divided into three parts: 1) the blade with the tip; 2) the front; 3) the back. When the tongue doesn’t work the blade with the tip is usually opposite the alveolar ridge. The front of the tongue is opposite the hard palate, the back of the tongue is opposite the soft palate. The movable organs of speech take an active part in the articulation of speech sounds. That’s why are also called active organs of speech. The fixed organs of speech are called passive. They serve as points of articulation. According to the work of the organs of speech all sounds are divided into vowels and consonants. This division is based mainly on auditory effect. Consonants are sounds which have noise and voice combined. Vowels are sounds produced with no constriction in the vocal tract. A vowel is a voiced sound produced in the mouth with no obstruction to the air stream. The air stream is weak, the tongue and the vocal cords are tense, the muscular tension is distributed more or less evenly throughout the mouth cavity and the pharynx. A consonant is a sound produced with an obstruction to the air stream. The organs of speech are tense at the place of obstruction. In the articulation of voiceless consonants the air stream is stronger, while in voiced consonants it is weaker. Vowels are sounds of pure musical tone, while consonants are either sounds in which voice prevails over tone or sounds in which tone prevails over tone (for example, sonorants).

Consonants They can be classified according to: 1) the type of obstruction; 2) the work of the vocal cords; 3) the position of the soft palate; 4) which organ of speech is involved and place of obstruction.

Classification of Consonants. Types of Obstruction. There are two types of articulatory obstruction: 1) complete; 2) incomplete. A complete obstruction is formed when two organs of speech come in contact with each other and the air passage through the mouth is blocked. An incomplete obstruction is formed when an articulation organ is very close to a point of articulation so as to narrow, or constrict, the air passage, but without blocking it. According to the type of obstruction English consonants are divided into occlusive and constrictive. Occlusive consonants are produced with a complete obstruction; the air passage in the mouth cavity is blocked. Constrictive consonants are produced with an incomplete obstruction.  Occlusive consonants may be noise and sonorants. Noise consonants are divided into plosives and affricates. In the articulation of plosive consonants the speech organs form a complete obstruction which is then quickly released with plosion: [p], [b], [t], [d], [k], [g]. In the production of affricates the speech organs form a complete obstruction which is then released slowly with a considerable friction occurring at the point of articulation: [t∫], [dʒ]. In the production of occlusive sonorants the speech organs form a complete obstruction in the mouth cavity which is not released. The soft palate is lowered and air escapes (passes) through the nasal cavity:[m], [n], [η]. Constrictive consonants are produced with an incomplete obstruction (by narrowing the air passage) and may be noise and sonorants. In the production of noise constrictive consonants the speech organs form an incomplete obstruction: [f], [v], [θ], [ð], [s], [z], [h], [∫], [ʒ]. In the production of constrictive sonorants the air passage is rather wide. The air passes through the mouth and doesn’t produce audible friction. Here tone prevails over noise. Constrictive sonorants may be median and lateral. In the production of median sonorants the air passes without an audible friction over the central part of the tongue. The sides of the tongue are raised: [w], [r], [j]. In the production of lateral sonorants the tongue is pressed against the alveolar ridge of the teeth and the sides of the tongue are lowered. They leave the air passage open along them: [l]. Another characteristic feature of English consonants is the place of articulation. The place of articulation is determined by the active organ of speech against the point of articulation. According to this principle English consonants are classed into: 1) labial; 2) lingual; 3) glottal. Labial consonants may be bilabial and labio-dental. Bilabial consonants are articulated by the two lips:[p], [b], [m], [w]. Labio-dental consonants are articulated with the lower lip against the upper teeth: [f], [v]. Lingualconsonantsare divided into: 1) forelingual; 2) mediolingual; 3) backlingual. Forelingual consonants are articulated by the blade of the tongue; the blade with the tip against the upper teeth or alveolar ridge. According to the position of the tip English forelingual consonants may be apical and cacuminal. Apical consonants are articulated by the tip of the tongue against the upper teeth or the alveolar ridge: [θ], [ð], [t], [d], [l], [n], [s], [z]. Cacuminal consonants are articulated with the tongue tip raised against the back part of the alveolar ridge: [r]. Mediolingual consonants are articulated with the front of the tongue against the hard palate: [j]. Backlingual consonants are articulated by the back of the tongue against the soft palate: [k], [g], [η]. Glottalare produced in the glottis: [h]. According to the articulation forelingual consonants are divided into: 1) dental; 2) alveolar; 3) palato-alveolar; 4) post-alveolar. Dental consonants are articulated against the upper teeth with the tip: [θ], [ð]. Alveolar consonants are articulated by the tip of the tongue against the alveolar ridge: [t], [d], [n], [l], [s], [z]. Palato-alveolar consonants are articulated by the tip and blade of the tongue against the alveolar ridge or the part of the alveolar ridge, while the front of the tongue is raised in the direction of the hard palate: [∫], [ʒ], [t∫], [dʒ]. Post-alveolar consonants are articulated by the tip of the tongue against the back part of the alveolar ridge: [r]. According to the force of articulation consonants are divided into fortis and lenis. English voiced consonants are lenis: [b],[d],[g],[dʒ],[v],[ð],[z],[ʒ],[m],[n],[ŋ],[w],[l],[r],[j]. English voiceless consonants are fortis:[p],[t],[k],[t∫],[f],[θ],[s],[∫],[h]. According to the position of the soft palate consonants are divided into oral and nasal. Nasal consonants are produced with the soft palate lowered while the air-passage through the mouth is blocked. As a result the air passes through the nasal cavity: [m], [n], [ŋ]. Oral consonants are produced when the soft palate is raised and the air passes through the mouth: [p], [b], [t], [d], [k], [g], [f], [v], [θ], [ð], [s], [z], [∫], [ʒ], [h], [t∫], [dʒ], [w], [l], [r], [j].

Vowels The quality of a vowel is known to be determined by the size, volume, and shape of the mouth resonator, which are modified by the movement of active speech organs (the lips and the tongue). The quality depends on: 1) stability of articulation; 2) tongue position; 3) lip position; 4) character of the vowel end; 5) length; 6) tenseness. The division of vowels into monophthongs and diphthongs is based on the stability of articulation. There are three possible varieties of articulation: 1) the position of the tongue is stable; 2) the position of the tongue is changeable; 3) weak position of the tongue. A monophthong is a pure unchanging vowel sound. In the production of monophthongs the organs of speech do not practically change their position throughout the duration of the vowels. A diphthong is a complex sound consisting of two-vowel elements pronounced as a single syllable. In the pronunciation of diphthongs the organs of speech start in the position of one vowel and glide gradually in the direction of another. The first element of an English diphthong is called the nucleus. It is strong, clear and distinct. The second element is rather weak. It is called the glide. In English there are three diphthongs with the glide towards [i], two diphthongs with the glide towards [u] and two diphthongs with the glide towards [e]. English diphthongs are characterized by the articulatory and syllabic indivisibility. That is neither the point of syllabic division nor a morpheme boundary can separate the glide from its nucleus. English native speakers perceive diphthongs as a single complex. That is proved by the fact that in languages that have no true diphthongs (Russian) the elements of such a sound complex can be easily separated from each other. A true triphthong should be indivisible by the point of syllable division and morphemic boundary. It should be a monomorphemic and monophonemic unity. The triphthongs in English don’t answer up to these requirements, because there is a point of syllabic division between the glide and the following neutral sound [ə].

e. g. flower [’flaʋə(r)]

The so called triphthongs can be regarded as vowel combinations consisting of diphthongs and the neutral vowel phoneme [ə]. Another important principle is the position of the tongue.In vowel production the tongue may move in a horizontal direction or in a vertical direction. Moving in the horizontal direction the bulk of the tongue may be in different parts of the mouth, while one of the parts of the tongue is higher than its other parts. According to the vertical movement of the tongue its raised parts may be at different heights in reference to the roof of the mouth. Different positions of the tongue determine the shape of the mouth resonator and the quality of sounds. According to the horizontal movement of the tongue (the position of the bulk of the tongue) vowels are divided into five groups: 1) front; 2) front-retracted; 3) central; 4) back; 5) back-advanced. Front vowels are produced with the bulk of the tongue in the front part of the mouth. The front of the tongue is raised in the direction of the hard palate, forming a large empty space in the back part of the mouth. The English front vowels are [i:], [e], [æ]. Front-retracted vowels are produced with the bulk of the tongue in the front part of the mouth, but some retracted. The front of the tongue is raised in the direction of the hard palate. There is only one front-retracted monophthong in English: [i]. Central vowels are those in which the central part of the tongue is raised towards the junction that is between the hard and soft palate. English central vowels are [ʌ], [з:], [ə]. Back vowels are produced with the bulk of the tongue in the back part of the mouth. The back of the tongue is raised in the direction of the soft palate, forming an empty space in the front part of the mouth. The English back vowels are [u], [u:], [ɔ:]. Back-advanced vowels are produced with the bulk of the tongue in the back part of the mouth but some advanced. The back of the tongue is raised in the direction of the front part of the soft palate. The English back-advanced vowels are [α], [ʋ]. According to the vertical movement of the tongue (the height of the raised part of the tongue) vowels are divided into three groups: 1) close (high); 2) open (low); 3) mid (half-open). Close (high) vowels are produced when one of the parts of the tongue comes close to the roof of the mouth and the air passage is narrowed. The English close vowels are [i],[i:], [u:]. Open (low) vowels are produced when the raised part of the tongue is very low in the mouth and the air passage is very wide. The English open vowels are [æ], [α:], [ʌ]. Mid (half-open) vowels are produced when the raised part of the tongue is halfway between its high and low positions. The English mid vowels are [e], [з:], [ə], [o:]. The next principle is the position of the lips. Traditionally three lips positions are distinguished: 1) spread; 2) neutral; 3) rounded. Lip rounding takes place due to physiological reasons, because the opening and the volume of the mouth changes when the lips are neutral or rounded. That increases the volume of the mouth resonator. Thanks to that we have a particular quality of a vowel. Another distribution of vowels is according to length. There can be long and short vowels. A vowel, like any sound, has its physical duration. By that we mean the time of its articulation. But in connected speech sounds are influenced by one another, and the duration depends on a lot of things: 1) its own length; 2) the accent (stress) of the syllable; 3) phonetic context; 4) the position of the sound in a syllable; 5) the position in a rhythmic group; 6) the position in a tone group; 7) the position in a phrase; 8) the position in the utterance; 9) the tempo if the whole utterance; 10) the type of pronunciation; 11) the style of pronunciation. The quantitative characteristics because of that are of secondary importance, as the quality of the sound remains unchanged. Some sounds have changed their quality in the course of time. It may be worth mentioning that the [æ] vowel being classed as historically short tends to be lengthened in Modern English, especially before lenis consonants [b], [d], [g], [dʒ], [m], [n], [z]. One more articulatory characteristic is tenseness. It characterizes the state of the organs of speech at the moment of articulation. Historically long vowels are tense, short vowels are lax.

Phoneme The phoneme is a minimal abstract linguistic unit which is realized in speech in the form of speech sounds. It is opposed to other phonemes of the same language to distinguish the meaning of morphemes and words. In the definition of the phoneme three aspects are combined: 1) material; 2) abstract; 3) functional (by this we mean the ability of a unit to differentiate). The phoneme is a functional unit. It serves to distinguish one morpheme from another, one word from another. It fulfills a distinctive function.

e. g. he was heard badly – he was hurt badly

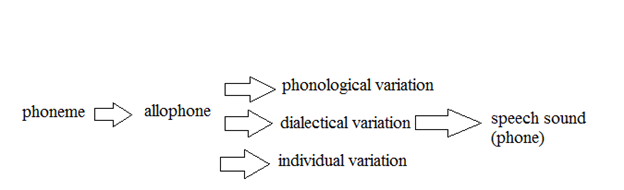

The phoneme is material, real and objective. It means that it is realized in speech of all English-speaking people in the form of speech sounds (allophones). The allophones which belong to the same phoneme are not identical in their articulation, but there exists some phonetic similarity between them. Let’s take the phoneme [d]. When it is not affected by preceding or following sounds it is plosive, forelingual, alveolar, lenis and epical. This variant of [d] is called principal. But there may be some changes of articulation under the influence of the neighboring sounds in different positions. Such allophones are called subsidiary. For example, [d] can be pronounced without a plosion: good dog. When [d] is followed by the labial [w] it becomes labialized: dweller. The sound [d] can also be palatalized before front vowels and the sonorant [j]: deal, day, did you. Allophones are positional variants of a phoneme. Allophones of the same phoneme have some similar articulatory features, but they show also phonetic differences. Allophones of the same phoneme never occur in similar phonetic context. They (their articulation) can be predicted by the phonetic environment. Sometimes allophones that are realized in speech do not coincide with those predicted by the phonetic environment. Allophones are modified by monostylistic, dialectical and individual factors.

The phoneme is an abstract unit. It is an abstraction from actual speech sounds. Native speakers do not differentiate between the allophones of the same phoneme, because this difference doesn’t distinguish meanings. But at the same time speakers realize that allophones of each phoneme possess some distinctive features which make this phoneme different from all other phonemes. The combination (unity) of these distinctive features is called invariant (relevant). Invariant characteristics are distinctive. Non-distinctive characteristics are those that serve to distinguish any meaning.

The Theory of the Phoneme

The so-called “functional” view regards the phoneme as the minimal sound (unit) which differentiates the meanings of words. This view is shared by many foreign linguists: Nikolai Sergeyevich Troubetzkoy (April 16, 1890 – Vienna, June 25, 1938), Leonard Bloomfield (April 1, 1887 – April 18, 1949), Roman Osipovich Jakobson (October 10, 1896, Moscow – July 18, 1982, Cambridge, Massachusetts), Morris Halle (born Morris Pinkowitz; July 23, 1923).

Trubetzkoy Bloomfield Jakobson Halle

The “physical” view regards the phoneme as a “family” of related sounds satisfying certain conditions: 1. The various members of the “family” must show phonetic similarity to one another, in other words be related in character. 2. No member of the “family” may occur in the same phonetic context as any other. This view was suggested by Daniel Jones (12 September 1881 – 4 December 1967).

Transcription Speech sounds may be presented graphically. The symbols of sounds differ according to the aim: 1) to indicate the phoneme; 2) to indicate the allophones. Mainly alphabetic symbols are accepted. Types of transcription: 1) phonemic, or broad (it provides special symbols for all the phonemes of a given language); 2) allophonic, or narrow (it gives symbols for each allophone). In our country two types of transcription are used. The first is based on the difference in quality and quantity between the vowel sounds (Daniel Jones). The second provides special symbols for all vowel symbols (V. A. Vasilyev).

Methods of Phonological Analysis Phonology is a branch of linguistics concerned with the systematic organization of sounds in languages. The aim of the phonological analysis is to identify the phonemes, to group them into similar classes and to find the relationship between them in the sound system of a language. Every language has its own system of phonemes. Each member of this system is determined by all other members of the system and doesn’t exist without them. There are some principals for the description of the phonemic structure of the language: 1) to determine the minimal units and to present them graphically by means of allophonic transcription (shine – shone). The idea of this principle is to single out minimal segments, to oppose them to one another in the same phonetic context which differs in one element only; 2) the arrangement of sounds into functionally similar groups. For that we may use two methods: a) distributional; b) semantic. Distributional analysis was created by structuralists. They group all the phonemes according to two laws: 1. Allophones of different phonemes occur in the same phonetic context. 2. Allophones of the same phoneme never occur in the same phonetic context. All sounds of a given language are combined and function according to a certain pattern characteristic of the language. For example, [h] never occurs at the end of word and [ŋ] never occurs at the beginning of the word. Semantic method is based on the rule that phonemes can distinguish words and morphemes when they are opposed to one another. This method consists in substitution of one sound for another. In this case we observe how phonetic context changes the meaning.

e. g. sin – din – win

Method of oppositional analysis. The phonemes of a language form a system of opposition in which any phoneme is usually opposed to other phonemes. There are three kinds of opposition: 1) single (it happens when the members of opposition differ in one feature)

e. g. back – pack similarities: occlusive, labial difference: [b] is voice, [p] is voiceless

2) double (it happens when the members of opposition differ in two features)

e. g. pen – den similarity: occlusive differences: [p] is labial and voiceless, [d] is voice and lingual

3) triple (it happens when the members of opposition differ in three features)

e. g. pen – then

Sound Alternation Sound alternations are sound variations in words, their derivatives and grammatical forms of words. These alternations are caused by assimilation, accommodation and reduction. Vowel alternations happen to be the result of their reduction in the unstressed position. They appeared in the historical development of the English language. They are used in present-day English to differentiate words, their derivatives and grammatical forms. Vowel alternations serve: 1) to distinguish forms of the irregular verbs (give – gave – given); 2) serve to distinguish singular and plural forms of nouns (man – men, woman – women, child – children); 3) to distinguish the parts of speech in correlated words (long – length, hot – heat). Consonant alternations serve: 1) to distinguish forms of the irregular verbs (build – built, send - sent); 2) to distinguish the parts of speech in correlated words (to speak - speech). Examples of vowel-consonant alternation: 1) life – live vowel alternation: [ɪ] – [aɪ] consonant alternation: [v] – [f] 2) breath – breathe vowel alternation: [e] – [i:] consonant alternation: [θ] – [ð] These types of alternations are sometimes supported by suffixation and the shifting of stress.

|

||

|

Последнее изменение этой страницы: 2018-05-31; просмотров: 894. stydopedya.ru не претендует на авторское право материалов, которые вылажены, но предоставляет бесплатный доступ к ним. В случае нарушения авторского права или персональных данных напишите сюда... |

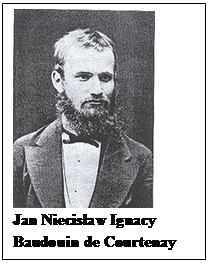

The “mentalistic” view regards the phoneme as an ideal mental image at which the speaker aims. Usually the speaker can’t pronounce the sounds ideally, because their articulation is influenced by the neighboring sounds. This view was originated by the founder of the phoneme theory, the Russian linguist I. A. Baudouin de Courtenay (13 March 1845 – 3 November 1929).

The “mentalistic” view regards the phoneme as an ideal mental image at which the speaker aims. Usually the speaker can’t pronounce the sounds ideally, because their articulation is influenced by the neighboring sounds. This view was originated by the founder of the phoneme theory, the Russian linguist I. A. Baudouin de Courtenay (13 March 1845 – 3 November 1929).

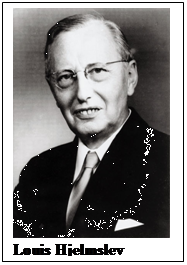

A stronger form of the “functional” approach is advocated in the so-called “abstract” view. It regards the phoneme as independent of the acoustic and physiological properties of speech sounds. According to this theory, the phoneme is an abstract conception existing only in the mind, not in reality. Speech sounds are phonetic realizations of these conceptions. This view of the phoneme was pioneered by Louis Hjelmslev (October 3, 1899, Copenhagen – May 30, 1965, Copenhagen) in 1963, and also by his associates in the Copenhaged Linguistic Circle, Hans Jørgen Uldall (1907,Silkeborg, Denmark – 1957,Ibadan, Nigeria) and K. Togby.

A stronger form of the “functional” approach is advocated in the so-called “abstract” view. It regards the phoneme as independent of the acoustic and physiological properties of speech sounds. According to this theory, the phoneme is an abstract conception existing only in the mind, not in reality. Speech sounds are phonetic realizations of these conceptions. This view of the phoneme was pioneered by Louis Hjelmslev (October 3, 1899, Copenhagen – May 30, 1965, Copenhagen) in 1963, and also by his associates in the Copenhaged Linguistic Circle, Hans Jørgen Uldall (1907,Silkeborg, Denmark – 1957,Ibadan, Nigeria) and K. Togby.